Initial tests confirm H5N1 avian influenza (bird flu) infection in a duck farm in Brandenburg, eastern Germany, authorities announced today.

Environment Ministry officials say that H5N1 was initially suspected when the poultry farm, which was carrying out its own tests, had positive results for avian influenza.

Environment Minister Anita Tack said: “All the necessary measures to contain and control (the H5N1 spread) have been initiated.” Samples were sent to counter-check to the Friedrich-Loeffler-Institute (FLI) on the Baltic island of Riems. The duck farm has been cordoned off and all its livestock will be culled, officials said.

The German government has ordered a full investigation. Experts do not know how the poultry became infected.

At the moment, the H5N1 bird flu virus is circulating in Indonesia, Cambodia and China. Some cases of infected birds among European wild bird populations have been reported.

On January 29th, 2013, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations warned that there is a serious risk of a repeat of the disastrous 2006 bird flu outbreaks if surveillance and control for H5N1 and other dangerous animal diseases is not strengthened.

FAO Chief Veterinary Office, Juan Lubroth, said: “The continuing international economic downturn means less money is available for prevention of H5N1 bird flu and other threats of animal origin. This is not only true for international organizations but also countries themselves. Even though everyone knows that prevention is better than cure, I am worried because in the current climate governments are unable to keep up their guard.”

It is vital that strict vigilance continues, Lubroth added, because large reservoirs of the H5N1 virus are still in existence in some Asian and Middle Eastern countries, where bird flu has become endemic. If proper controls are not maintained, avian influenza could spread around the globe and affect 63 countries as it did seven years ago.

It makes economic sense to invest more on bird flu prevention, given the massive toll a full-scale pandemic can inflict. From 2003 to 2011, over 400 million domestic chickens and ducks were either killed by the disease or culled, costing the global economy approximately $20 billion.

Between 2003 and 2011, H5N1 infected over 500 humans, of whom over 300 died, says the World Health Organization.

Lubroth said: “I see inaction in the face of very real threats to the health of animals and people. This is all the more regrettable as it has been shown that appropriate measures can completely eliminate H5N1 from the poultry sector and thus protect human health and welfare. Domestic poultry are now virus-free in most of the 63 countries infected in 2006, including Turkey, Hong Kong, Thailand and Nigeria. And, after many years of hard work and international financial commitment, substantial headway is finally being made against bird flu in Indonesia.”

It is still very hard for a human to become infected with the H5N1 avian influenza virus, and even rarer for one person to infect another.

Scientists, doctors and public health officials worry that if a human who is already infected with normal seasonal human flu becomes infected with avian flu, the avian flu virus may exchange genetic data with the human flu virus and acquire its ability to become easily transmissible from person-to-person. A bird flu virus that is easily human-transmissible could have devastating consequences.

Avian influenza has a very high death rate, up to 50% of infected people who get ill die. If bird flu became a pandemic, the death toll could be enormous.

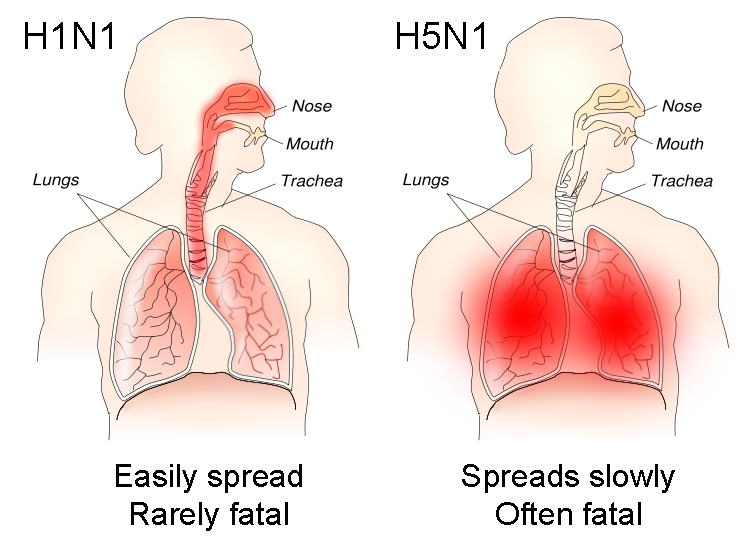

The H5N1 virus strain has to get deep into the lung to infect a human. This feature makes it both more deadly and less transmissible. If a person has an infection deep down in the lungs, fewer viruses are emitted when they cough and sneeze (compared to those with upper respiratory tract infections).

Seasonal human flu (H1N1) infects the upper respiratory tract. Bird flu (H5N1) infects the lower respiratory tract, making it more lethal but less human transmissible.

If a mutated bird flu virus managed to infect the upper respiratory tract as well, infected people’s sneezes and coughs would emit more viruses into the air, making it easier to infect others. People nearby would get ill more easily, because the virus would not need to go deep into the lung to cause illness.

Two papers, published in May/June 2012, showed the pandemic potential of H5N1. One paper identified four genetic changes a virus would need to undergo in order to become easily human transmissible, the other paper identified five. Another paper suggested that some of these changes are already occurring.

If bird flu outbreaks can be kept to a minimum, the likelihood of H5N1 coming into contact with H1N1 and mutating is smaller. WHO says that “controlling bird flu outbreaks and eliminating them as soon as possible is a top priority for public and global health.”

Written by Christian Nordqvist