Researchers from the University of Montreal have discovered that the amino acid asparagine is essential for healthy brain development in children. They have also discovered that while other organs in the body can draw asparagine from dietary sources, the brain needs the local synthesis of the amino acid to function properly.

Senior co-author of the study Dr. Jacques Michaud explains:

“The cells of the body can do without it because they use asparagine provided through diet. Asparagine, however, is not well transported to the brain via the blood-brain barrier.”

Dr. Michaud and his colleagues linked a specific gene variant with a deficiency of the enzyme, asparagine synthetase, which is responsible for synthesizing the amino acid asparagine.

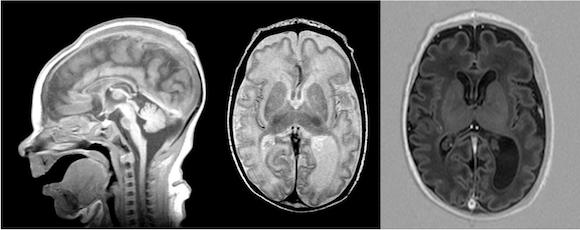

This extremely rare genetic disease causes a variety of symptoms, including intellectual disability, refractory seizures and cerebral atrophy, which can lead to death.

Dr. Michaud continues:

“In healthy subjects, it seems that the level of asparagine synthetase in the brain is sufficient to supply neurons. In individuals with the disability, the enzyme is not produced in sufficient quantity, and the resulting asparagine depletion affects the proliferation and survival of cells during brain development.”

However, children who are carriers of this mutation suffer to varying degrees. One family in Quebec has lost three infants below the age of 1 year to the disease, while two other siblings are alive and healthy.

Dr. Michaud is optimistic that his study can be used to develop treatments for this rare but catastrophic disease. He says:

“Our results not only open the door to a better understanding of the disease, but they also give us valuable information about the molecular mechanisms involved in brain development, which is important for the development of new treatments.”

Infants born with this gene could be given supplements to ensure an adequate level of asparagine in the brain and the latter’s healthy development. Dr. Michaud cautions:

“The amount of supplementation remains to be determined, as well as its effectiveness. Since these children are already born with neurological abnormalities, it is uncertain whether this supplementation would correct the neurological deficits.”

To date, nine children from four different families have been identified as carriers of this genetic mutation. They are three infants from Quebec, three from a Bengali family living in Toronto and three Israeli children, whose symptoms are not as severe.

But Dr. Michaud told Medical News Today that “there are certainly several other children or adults with this condition, but they have not yet been identified.”

Dr. Michaud’s team discovered the genetic mutation by comparing the complete DNA of the Quebec family’s children with symptoms of the disease. The researchers then identified children from other families who carried the single candidate gene. The gene was revealed only in the affected children but not in the unaffected children of the families studied.

Dr. Michaud concludes:

“We are not at the verge of a miracle drug, but we at least know where to look.”