This month, for the first time, the US has been confronted with two confirmed cases of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome virus. Though public health officials are taking great steps to prevent spread of the illness, the World Health Organization say the conditions for a Public Health Emergency of International Concern have “not yet been met.”

On May 2nd, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed the first case of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in a traveler from Saudi Arabia who landed in Chicago, IL, before taking a bus to Indiana.

Then, on May 12th, a second – unrelated – case of the virus was confirmed in another traveler to the US. This time, it was a health care worker from Saudia Arabia who landed in Boston, MA, before traveling by plane to Atlanta, GA, and then to Orlando, FL.

“We’ve anticipated MERS reaching the US, and we’ve prepared for and are taking swift action,” said CDC Director Dr. Tom Frieden after the first confirmed case. “This case reminds us that we are all connected by the air we breathe, the food we eat, and the water we drink.”

He added that in this “interconnected world we live in, we expected MERS-CoV to make its way to the US.” As such, the CDC have been preparing for this since 2012, when the first case was reported in Saudi Arabia.

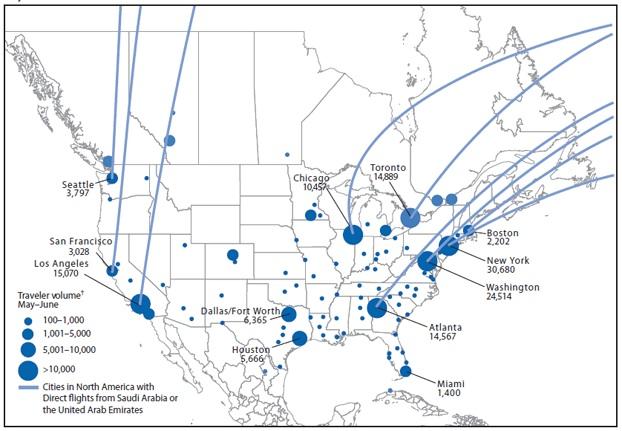

This image shows points of entry and volume of travelers on flights to the US and Canada from Saudi Arabia and the UAE during May-June 2014.

Image credit: BioMosaic, CDC

Including these two cases in the US, the World Health Organization (WHO) report that there have so far been 536 laboratory-confirmed cases of MERS-CoV infection in 12 countries, and all reported cases have come from seven countries in the Arabian Peninsula.

Most individuals with the virus have developed severe acute respiratory illness, and 145 people have died. Unfortunately, there is currently no available vaccine or treatment for the virus, and officials are unsure of where the virus came from or how it spreads.

After the second US outbreak, public health officials began reaching out to health care professionals, family members and airline officials to notify travelers who may have been in close contact with the patient during any of the flights.

In a newly released

The organization says individuals who have recently traveled may seek medical care far from cities that are served by international flight connections; therefore all health care professionals should be cautious and should “be prepared to consider, detect and manage cases of MERS.”

To help health care professionals, WHO officials have recently posted

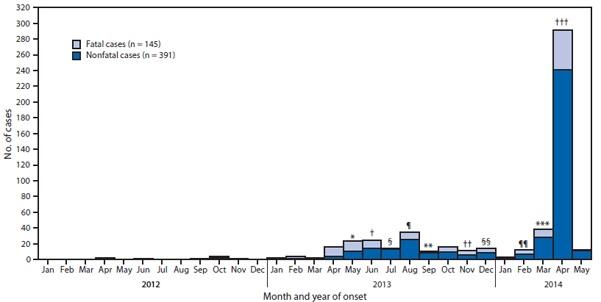

The graph above shows the number of confirmed cases of MERS reported by the WHO as of May 12, 2014, by month of illness onset worldwide.

Image credit: CDC

A

But they did admit their concern about the circumstances had “significantly increased,” based on the recent rise in cases, weakness in prevention and control, and gaps in critical information.

The CDC say health care providers should contact state or local health departments if they have any questions.

In light of the recent increase in MERS cases, the CDC have updated their travel advice and have upgraded their travel notice to a Level 2 Alert, which involves extra precautions for people who plan to work in health care settings in countries in or near the Arabian Peninsula.

Additionally, the organization recommends that all travelers to such countries protect themselves by washing their hands often and avoiding contact with people who are ill.

Dr. Frieden adds:

“That’s one of the reasons we focus on helping other countries find and stop emerging infections such as MERS promptly and preventing them wherever that’s possible. This is one of the reasons that we’ve recently stepped up our efforts to improve global health protection and global health security because we really are all connected by the air we breathe, by the water we drink and by the food we eat and by the airplanes that we ride on.”

Given that there are currently not any vaccines or means of combatting the MERS virus, the question of what is being done is a natural one to ask.

Researchers from Purdue University in Indiana have recently announced they are creating molecules designed to “shut down” the MERS-CoV virus.

Prof. Andrew Mesecar, who leads the team, says they are creating molecules that block a “key enzyme that allows the virus to live.” He continues:

“This enzyme has a big mouth that, in a way, allows it to chew up other proteins the virus needs to live. How do we stop a big mouth from chewing things up? We stuff it full of something else. That is what the molecules we invent do. If you can shut down this critical enzyme, you can effectively shut down the virus.”

Meanwhile, a company called QuantuMDx Group has sought to tackle the issue of outbreaks with their new device, called the Q-POCTM. This provides the accuracy of a referral laboratory at the patient’s side, at a fraction of the cost and in a shorter time period.

By breaking open cells to analyze DNA while a Q-filter separates the mixture in 15 minutes, it can detect viruses much faster than the days the process currently takes, which could help in reporting illnesses to health care bodies before they become widespread.

Speaking with Medical News Today, Jonathan O’Halloran from QuantuMDx Group said:

“By networking the data, along with GPS coordinates from these devices, we will be able to monitor all pathogens that affect humans and allow us to understand the dynamics of new threats and the emergence of new drug-resistance mutations.

By doing this in real-time, rather than taking weeks or months to identify the pathogens, we can mobilize resources to contain outbreaks quicker, before they have the opportunity to spread.”

He added that, “by understanding the specific genotypes in different populations, we will be able to manage our use of anti-infective therapeutics better, providing another tool in the fight.”