While essential to human life, a new study finds that aspects of oxygen metabolism may promote cancer.

Lung cancer is responsible for 27% of all cancer deaths in the US, claiming an estimated 160,000 lives per year. While almost 90% of lung cancer cases are linked to smoking, the new study suggests that atmospheric oxygen may play a role in lung carcinogenesis.

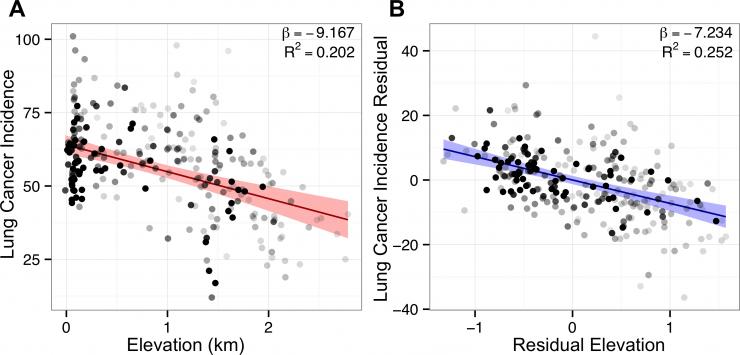

Exploring the inverse relationship of oxygen concentration with elevation, researchers found lower rates of lung cancer at higher elevations, a trend that did not extend to non-respiratory cancers, suggesting that carcinogen exposure occurs via inhalation.

Oxygen is highly reactive, and even when it is cautiously and rapidly consumed by our cells, it results in reactive oxygen species, which can lead to cellular damage and mutation.

While oxygen comprises 21% of the overall atmosphere, lower pressure at higher elevations results in less inhaled oxygen – an effect that notoriously frustrates athletes at high altitudes.

For example, across US counties, elevation differences account for a 34.9% decrease in oxygen from Imperial County, CA (-11 m) to San Juan County, CO (3,473 m).

The research, published in the peer-reviewed open access journal PeerJ, was conducted by Kamen P. Simeonov from Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, and Daniel S. Himmelstein from Biological & Medical Informatics, University of California, San Francisco, CA.

Simeonov and Himmelstein investigated whether inhaled oxygen could be a human carcinogen by comparing cancer incidence rates across counties of the elevation-varying Western US.

The research revealed that as county elevation increased, lung cancer incidence decreased.

The effect of elevation was significant with incidence of lung cancer, decreasing by 7.23 cases per 100,000 individuals for every 1,000-meter (3,281 ft) rise in elevation, equating to approximately 13% of the mean lung cancer incidence of 56.8 cases per 100,000 individuals. A variety of statistical techniques attested that the association was not due to chance.

The authors point out, however, that the observed association does not prove that oxygen causes lung cancer.

In the left-hand panel, lung cancer incidence is plotted against elevation for Western US counties. Darker counties have higher populations and thus lower observational errors. The right-hand panel shows the association when accounting for additional factors, such as smoking and education.

Image source: Perelman School of Medicine

The researchers performed extensive analysis to examine confounding potentials, with their model accounting for risk and demographic variables including smoking prevalence and education. The observed association was consistent across population subgroups, states and models that included a range of additional factors.

Three of the remaining most common cancers in the US – breast, colorectal and prostate – were also evaluated. The association of elevation with these non-respiratory cancers was either weak or absent, supporting the hypothesis of elevation as an inhaled risk factor.

Environmental correlates of elevation, such as sun exposure and pollution measures, produced significantly inferior predictions of lung cancer incidence when compared with elevation itself.

Two previous epidemiological reports, examining elevation as a confounder, suggested that elevation-dependent oxygen variation was responsible for lower cancer mortality at high elevation. In contrast to these two past studies, the current study was specifically designed to calculate the effect of elevation and benefited from a recent proliferation of high-quality county-level data.

The study evaluated over 30 variables and included 260 Western US counties. Using high-resolution census data, the researchers measured elevation values that reflected population dispersion within each county and calculated the atmospheric exposure of each county’s populace.

Simeonov and Himmelstein anticipate that future research in the field will focus on oxygen’s role in human carcinogenesis. They say that the in-depth investigation of diverse regions and individual-level datasets would contribute further epidemiological evidence.

If future examinations confirm oxygen-driven tumorigenesis, the medical implications could be large. The authors explain:

“Were the entire United States situated at the elevation of San Juan County, CO (3,473 m), we estimate 65,496 fewer new lung cancer cases would arise per year.”

While the researchers do not expect or recommend individuals to relocate based on this discovery, identifying a universal and major risk factor could provide new insights into lung cancer etiology. From these insights, better treatments and preventative measures may arise.

Medical News Today recently reported that women who work rotating night shifts for 5 years or more may be at increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality, while working such shifts for 15 years or more may raise the risk of lung cancer mortality.