Competition among doctors' offices, urgent care centers and retail medical clinics in wealthy areas of the U.S. often leads to an increase in the number of antibiotic prescriptions written per person, a team led by Johns Hopkins researchers has found.

"We found that both the number of physicians per capita and the number of clinics are significant drivers of antibiotic prescription rate," the researchers say in a report on the findings published online ahead of print in the Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy.

"The increase in the number of antibiotic prescriptions written in wealthy areas appears to be driven primarily by increased competition among doctors' offices, retail medical clinics and other health care providers as they seek to keep patients satisfied with medical care and customer service," says lead study author Eili Klein, Ph.D., an assistant professor of emergency medicine in the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and a member of the Johns Hopkins Center for Advanced Modeling in the Social, Behavioral and Health Sciences.

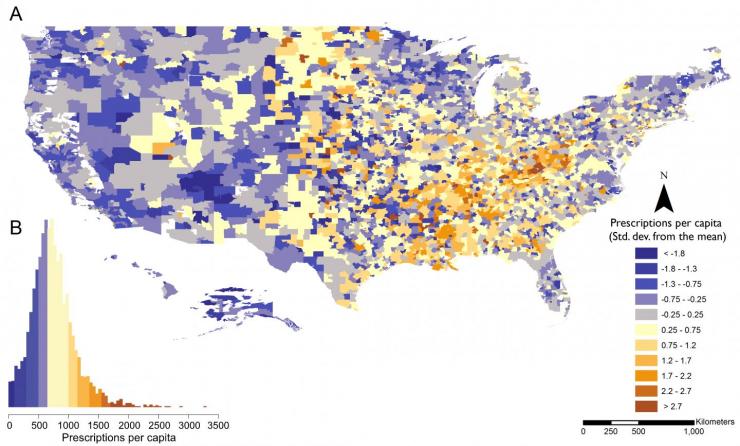

On a regional basis, the highest per capita rates of antibiotic prescriptions were found in the southeastern U.S. and along the West and East coasts.

At a more metropolitan scale, notably high rates of the prescribing of antibiotics were found in Manhattan, southern Miami and Encino, California, among other areas. Overall, the researchers' analysis revealed highly variable prescription rates across the United States.

The team's comparative analysis of data for the years 2000 and 2010 were collected from the U.S. Census Bureau and the IMS Health Xponent database, which tracks prescriptions dispensed at the ZIP code level.

The data showed that the presence of retail medical clinics, like those found in chain drug and "super" stores, and of urgent care centers increases the prescribing rate, but the effect was different in wealthy versus poor areas.

In wealthy areas, the presence of clinics correlated to an increase in the prescribing rate of physicians.

However, while the presence of retail or urgent care clinics in poorer areas increased access to health care, it did not generate competition among providers that resulted in higher prescribing behavior by physicians' offices.

The findings, according to the research team, add to the growing body of evidence indicating that social and economic factors are contributing to the overuse of antibiotics in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that such overuse is a major factor in the spread of antibiotic resistance and a worldwide health threat resulting in 23,000 deaths a year in the U.S. alone.

The researchers say their results also suggest that in wealthy areas, residents may be more able and likely to shop for a health care provider willing to write a prescription than is the case in poorer areas.

"We were surprised to find in this study that there is a really strong suggestion in the data that physicians are competing with other physicians, and they are doing that through the mechanism of prescribing antibiotics," says Klein.

"It speaks to the fact that health care is a business," he adds. "But it also underscores that there is a lot of pressure on doctors to prescribe antibiotics -- even when they aren't 100 percent certain they are necessary."

One of those pressures, Klein says, is the time available to spend with each patient. There are reliable estimates, he notes, that it takes a doctor five minutes to see a patient who isn't feeling well and write a prescription for an antibiotic, but it takes 15 minutes to explain to the patient why they don't need one.

Klein says physicians' offices also face pressure from patients shopping around for care or from retail medical clinics that may offer a prescription if a physician office doesn't.

"These are all real pressures contributing to a public health crisis driven by the overuse of antibiotics," says Klein, who has published other studies looking at how social and economic interactions and trends are contributing to antibiotic resistance.

Klein cautioned that the new study did not seek to determine any possible link between antibiotic resistance rates and high prescribing rates in specific ZIP codes marked by such behavior, reliable ZIP code-specific data on antibiotic resistance are not available.

The authors hope that the study contributes to a greater understanding of the many factors that contributing to antibiotic overuse, and that others will use the study findings to develop solutions to help curb inappropriate antibiotic prescribing behavior.

For example, Klein says, the findings could be used to help guide the development of a program to educate physicians by showing how their antibiotic-prescribing behavior compares to others on a local, regional or national level.

This map shows prescriptions per capita.

Credit: Johns Hopkins Medicine