A study accuses the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of allowing seafoods with unsafe levels of contaminants to enter the food chain after the BP oil disaster. A study carried out by the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) and published in the peer-reviewed Environmental Health Perspective reports that the FDA underestimated the risk of cancer from accumulated contaminants in the seafood – especially the risk for pregnant mothers and children who live in the area.

In some cases, the FDA let through foods with 10,000 times too much contamination. The federal Agency is also accused of not identifying the risks for children and pregnant mothers. It appears the FDA used faulty assumptions and obsolete risk assessment methods.

The NRDC has today filed a petition urging the FDA to set limits on PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) that can be present in seafood. It is vital that the country’s pregnant mothers, children, and individuals with high seafood consumption be protected, the NRDC added.

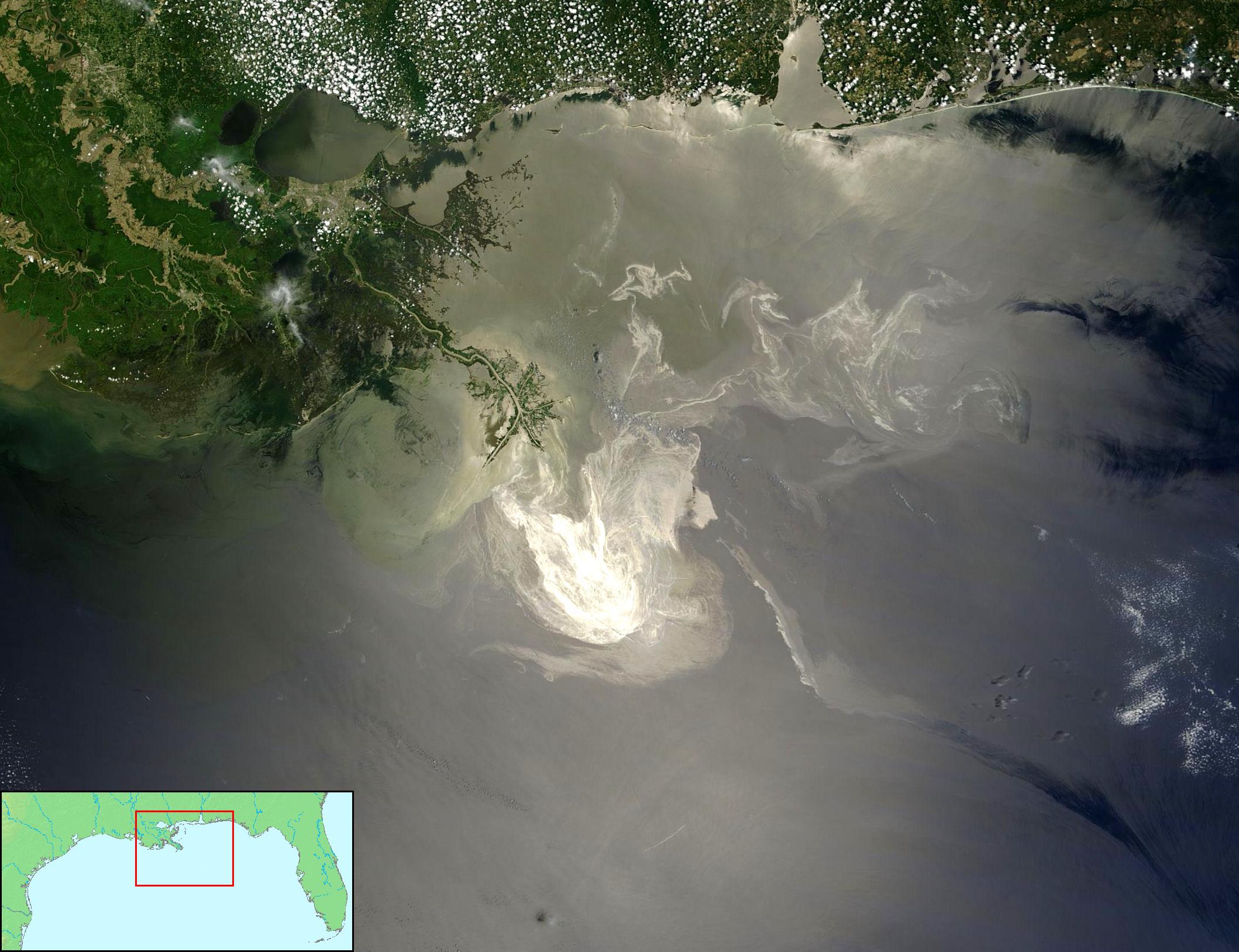

BP oil spill disaster in the Gulf of Mexico – (NASA’s Terra satellite on May 24, 2010)

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, also known as PAHs, poly-aromatic hydrocarbons or polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons are powerful atmospheric pollutants, consisting of fused aromatic rings that contain no heteroatoms or carry substituents. The simplest form of PAH is naphthalene. PAHs can be found in tar deposits, coal and oil; they are also produced as a by-product of burning fossil or biomass fuels.

PAHs are of concern to human health because some of their compounds have been linked to cancer risk – there is also talk of their mutagenic (can cause genes to mutate) and teratogenic (can cause birth defects) harms. PAHs may be present in cooked foods – cooking meat at very high temperature, such as barbecuing or grilling can raise their PAH levels. Smoking fish may also have a similar effect. PAHs can also cause liver damage.

One of the researchers, Miriam Rotkin-Ellman, said:

“Our findings add to a long list of evidence that FDA is overlooking the risks from chemical contaminants in food. We must not wait for people to get sick or cancer rates to rise, we need FDA to act now to protect the food supply.”

The authors of the study concluded:

“FDA risk assessment methods should be updated to better reflect current risk assessment practices and to protect vulnerable populations such as pregnant women and children.”

In her blog, Rotkin-Ellman wrote that the FDA had calculated that 123,000 micrograms of naphthalene per kg of shrimp was a safe level for human consumption. According to the calculations of her team, the limit should have been 5.91 micrograms if pregnant women and children who eat a lot of seafood are to be protected. Even for non-pregnant adults, they worked out that the safe limit should only be 46.99 micrograms of naphthalene per kg of shellfish.

According to the scientists calculations, if 1,000 pregnant women and their children consumed Gulf seafood with contamination limits set by the FDA, 20 of the children born to those women would be at considerable risk of cancer caused by the contamination.

Rotkin-Ellman wrote:

“This is not public health protection. Major reforms are needed at FDA to better safeguard our food supply.”

When Rotkin-Ellman and team gathered data on testing of PAH levels of shellfish after the BP oil spill, they found that up to 53% of the tested shrimps had PAH levels above their own revised safety limits for pregnant mothers and children (who eat a lot of shellfish).

Rotkin-Ellman added:

“Instead of saying it was safe for everyone to eat, pregnant women and children should have been warned and advised to reduce their Gulf shellfish consumption.”

The scientific team say they have been concerned about this issue for some time. They could not understand how the FDA had deviated so much from the guidelines of other agencies and even its own prior practice after previous oil spills.

To find out why, they asked the FDA for documents under the FOIA (Freedom of Information Act). After a year of non-stop wrangling to get the appropriate documents, through the FOIA request, they discovered that the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) had proposed stricter health protections from contamination – these proposals were ignored. Even some FDA staff, apparently, said the protections should be stronger.

In an email, the EPA told the FDA that it underestimated the risks for many seafood consumers, particularly those living on the Gulf Coast.

Written by Christian Nordqvist