More and more, the medical world is being merged with technology to improve diagnosis, prevention and treatment of health conditions. Now, researchers from Oxford University in the UK have developed a computer algorithm that can analyze photographs and diagnose which children have a rare genetic disorder.

The researchers, who publish their results in the journal eLife, say their computer program recognizes facial features in photos, looks for facial structures resembling various conditions – including Down syndrome, Angelman syndrome or progeria – and returns potential matches ranked by likelihood.

According to the team, although genetic disorders are rare individually, they collectively affect almost 8% of people, and about one third of these people have symptoms that reduce their quality of life.

There are over 7,000 known inherited disorders, but only a minority of patients with a suspected disorder receive a clinical or genetic diagnosis.

The tricky thing about diagnosing a suspected developmental disorder is that frequently, clinical geneticists need to come to a conclusion based on facial features, follow-up tests and their own individual expertise.

Lead researcher Dr. Christoffer Nellåker, of the Medical Research Council Functional Genomics Unit at the University of Oxford, says:

“A diagnosis of a rare genetic disorder can be a very important step. It can provide parents with some certainty and help with genetic counseling on risks for other children or how likely a condition is to be passed on.”

He adds that a diagnosis can “also improve estimates of how the disease might progress, or show which symptoms are caused by the genetic disorder and which are caused by other clinical issues that can be treated.”

The team notes that it is believed between 30-40% of rare genetic disorders include some change in the face and skull, most likely because so many genes are implicated in facial and cranial development as a baby grows in the womb.

To make diagnosis more efficient, the team aimed to teach a computer to objectively carry out such assessments.

They first collected a database of 2,878 images, which included 1,515 healthy controls and 1,363 photos for eight known developmental disorders.

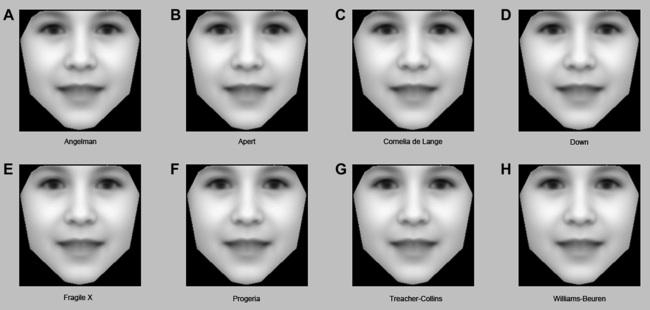

Using the latest in computer vision and machine learning, their algorithm progressively learns which facial features to consider and which to ignore, using a growing bank of photos of people diagnosed with different disorders.

After first recognizing faces in ordinary photographs, the program then accounts for variations in lighting, image quality, background, pose, facial expression and identity.

By recognizing corners of eyes, nose, mouth and other features, the program builds a description of the face structure and compares this with what it has learned from other photos. It then automatically clusters together patients who share the same condition.

The above image shows an average face taking on the average facial features of eight rare genetic disorders that have been built from a growing bank of photographs of people diagnosed with different syndromes.

Image credit: Christoffer Nellåker/Oxford University

The researchers say that as their algorithm learns more with more data, it makes better diagnosis suggestions for a photo where it has previously seen lots of other photos of people with that same syndrome.

However, the team also says the program clusters patients together where no documented diagnosis exists, which could potentially help in identifying ultra-rare genetic disorders.

“A doctor should in future, anywhere in the world, be able to take a smartphone picture of a patient and run the computer analysis to quickly find out which genetic disorder the person might have,” says Dr. Nellåker.

“This objective approach could help narrow the possible diagnoses, make comparisons easier and allow doctors to come to a conclusion with more certainty,” he adds.

The study was funded by the MRC, the Wellcome Trust, the National Institute for Health Research Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, and the European Research Council.