Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SJIA), or “Still’s disease,” is a rare autoinflammatory disease affecting different body organs and systems. The disease occurs in childhood but can continue into adulthood.

While there is no cure for SJIA, treatments can help to bring about disease remission, resulting in few or no symptoms.

This article outlines the prevalence of SJIA and lists some of its symptoms and health effects. It also considers the disease causes and risk factors and provides information on diagnosis, treatment, and outlook.

Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SJIA) is a rare subtype of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). The American College of Rheumatology reports that JIA is a chronic form of arthritis that affects around 1 in every 1,000 children.

According to the Arthritis Foundation, around 10% to 20% of children with JIA have the rare SIJA subtype.

The main symptoms of SJIA are outlined below:

- Fever: One of the first signs of SJIA is a recurrent high fever of 103ºF or higher, which tends to follow a regular pattern. For most children, the fever spikes in the evening. For others, it may occur in the morning or twice a day. The fever returns to normal following the spike.

- Rash: Children with SJIA may develop a flat, pale, or pink rash on their trunk, arms, or legs. The rash is often not itchy. It typically occurs alongside fever spikes and may persist for minutes or hours.

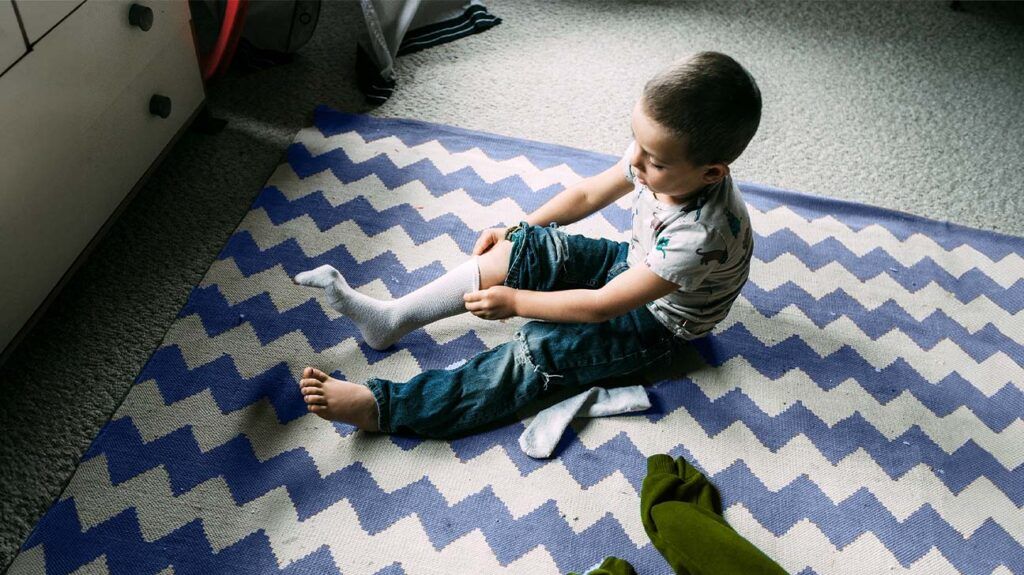

- Joint symptoms: Children with SJIA typically develop arthritis symptoms, such as joint pain, swelling, and stiffness. These symptoms may develop in a single joint but usually occur in multiple joints, such as the wrists, ankles, and knees. Parents and caregivers may notice the following signs of arthritis in the child:

- limping

- stiffness in the morning or after a long nap

- a sudden drop in activity levels

Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis can cause a broad range of health complications. These are outlined below.

Macrophage Activation Syndrome (MAS)

MAS is a severe and potentially life threatening inflammatory response. The Arthritis Foundation reports that it affects around 10% of children with SJIA.

The immune system consists of two parts: the innate immune system (IIS) and the adaptive immune system (AIS).

The IIS produces immune cells called macrophages and T-lymphocytes, which work together to launch generalized attacks against invading organisms. The AIS produces specific antibodies to fight specific organisms.

In MAS, the IIS goes into overdrive, producing large numbers of macrophages and T-lymphocytes. These immune cells flood the body with proteins called inflammatory cytokines, which promote inflammation. High levels of inflammation can damage the body’s organs, including the heart, liver, kidneys, and spleen.

Experts are not sure what causes the IIS to mount an abnormal response in MAS. However, contributing factors include:

- infections, which account for around 50% of MAS cases

- disease flares

- certain drugs, including those that doctors use to treat SJIA

- certain gene mutations

Lung and heart problems

Children with SJIA may experience lung and heart problems, such as pulmonary artery hypertension (PAH), interstitial lung disease (ILD), and pericarditis, which refers to fluid around the heart.

PAH

PAH is the medical term for high blood pressure that affects the lungs and the right side of the heart. It occurs when the tiny arteries in the lungs thicken and narrow, blocking blood flow through the lungs.

This causes the heart to pump harder to push blood through the damaged arteries.

Symptoms of PAH include:

- shortness of breath

- heart palpitations

- chest pain

- cough

- hoarse voice

- fatigue

- episodes of dizziness and fainting

- swelling of the feet and legs or other parts of the body

- bluish coloration of the lips and fingers (cyanosis)

ILD

ILD is the umbrella term for a group of diseases that can cause scarring or “fibrosis” of the lungs. Such diseases cause breathing difficulties and impair oxygen delivery to the body’s cells.

The most common symptom of ILDs is shortness of breath. Other potential symptoms include:

- dry cough

- chest discomfort

- fatigue

- unexplained weight loss

Bones and joints

In SJIA, persistent inflammation can damage the joints, impairing their range of motion and overall function.

Other bone and joint issues that may develop because of SJIA include:

- issues with the temporomandibular joints (TMJs) in the jaw, which may lead to an underdeveloped chin

- fusion of the cervical spine, which may cause neck problems

- unusual or asymmetric bone development

- stunted growth

Children who take corticosteroids to help treat their SJIA may also experience unusual or stunted growth as a side effect of these medications. Continued use of corticosteroids may also lead to a bone disease called osteoporosis, which causes bones to become weak and brittle and prone to fracture.

High blood pressure

Both SJIA and the corticosteroid treatment doctors may prescribe to treat the condition can lead to atherosclerosis. This is a condition in which fatty deposits accumulate inside the artery walls, causing the arteries to narrow.

Blood pressure increases as the heart pumps harder to move blood through the narrowed arteries. Over time, this process can result in high blood pressure (hypertension).

SJIA appears to be an autoinflammatory condition involving overactivity of the IIS. This theory is supported by the fact that children with SJIA typically have high blood levels of two inflammatory cytokines: interleukin-1 (IL-1) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). Both can cause high levels of inflammation throughout the body.

Experts are not sure exactly what causes SJIA. However, most experts believe that some children have a genetic predisposition to SJIA and that an environmental factor then triggers the condition.

A 2019 review lists some potential environmental risk factors for SJIA, including:

- viral and bacterial infections

- antibiotic usage

- cesarean section delivery

The diagnostic procedure for SJIA typically entails the following:

- a medical history assessment

- a physical examination to check for joint issues, limb length, overall growth, and swollen lymph nodes

- imaging tests such as MRI or ultrasound scans, which check for inflammation in the joints or organs

- blood tests to check for inflammatory markers, and other potential signs of SJIA, such as:

- extremely high white blood cell and platelet counts

- extremely high levels of ferritin

- severe anemia

There is currently no cure for SJIA, but treatments can help send the disease into remission. Once in remission, the disease is inactive, and the person experiences few or no symptoms.

Some of the treatment options for SJIA are outlined below.

Medications

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are typically the first-line treatment for SJIA.

If these drugs are ineffective within a week, doctors may prescribe a temporary high dose of corticosteroids to alleviate systemic inflammation and associated symptoms rapidly.

Once the symptoms of SJIA have resolved, doctors may prescribe nonbiologic, conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) alone or in combination with biologics. This approach may help to slow joint damage.

Non-drug therapies

Regular exercise can provide the following benefits for children living with SJIA:

- building muscle strength

- maintaining joint function and flexibility

- increasing energy levels

- reducing pain

- boosting a child’s confidence in their physical abilities

Most children with well-managed SJIA are typically able to participate fully in sporting activities, though children experiencing an active disease flare may need to limit certain activities until they are feeling better.

A physical therapist can provide further information about appropriate physical activities for children with SJIA.

A

At the time of the final follow-up visit, the children had a median age of 16.9 years, and the study authors reported the following:

- 47% of children were in remission and off medications

- 25% of children were in remission while on medications

- 27% of children had active disease, and 51% of these children were taking at least one anti-rheumatic medication

The study noted that children with SJIA had the highest drug-free remission rates, with 70% of children sustaining remission without medications.

A

Below are some answers to frequently asked questions about SJIA.

What is the difference between systemic juvenile arthritis and still’s disease?

There is no difference between SJIA and Still’s disease. These two terms refer to the same condition.

What is the difference between polyarticular and systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis?

Polyarticular JIA (PJIA) and SJIA are two different forms of JIA, both of which can affect children of any age.

The United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS) reports that PJIA is the second most common form of JIA after oligo-articular JIA, and the symptoms are similar to those of adult rheumatoid arthritis.

SJIA is an autoinflammatory disease, while PJIA is an autoimmune disease in which the body’s own immune system mistakenly attacks healthy joints.

A person should contact a doctor if their child shows signs or symptoms of SJIA, such as:

- a high fever that tends to follow a regular pattern and returns to normal after the spike

- a fleeting skin rash on the trunk, arms, or legs

- joint pain, swelling, or stiffness

- any other concerning symptoms

A doctor can carry out a full physical examination and order any necessary tests to determine the cause of the symptoms.

Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SJIA) is a rare form of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA).

In SJIA, the body’s innate immune system releases an excessive number of proteins called inflammatory cytokines, which cause widespread inflammation throughout the body.

Symptoms of SJIA typically include a high fever, a transient skin rash, and joint pain, swelling, or stiffness.

The condition may cause other health issues, such as high blood pressure and heart and lung problems, without treatment.

While there is currently no cure for SJIA, medications can cause the disease to go into remission.