Damage to the brain caused by concussion can last for decades after the original head trauma, according to research presented at a AAAS (American Association for the Advancement of Science) Annual Meeting in 2013.

The finding comes to light at the same time as 4,000 former football players file lawsuits alleging that the National Football League failed to protect them from the long-term health consequences of concussion.

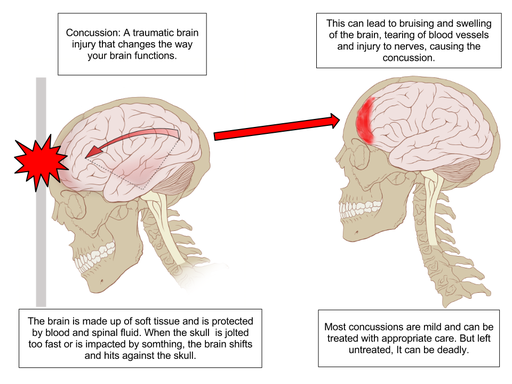

Concussion causes temporary loss of brain function leading to cognitive, physical and emotional symptoms, such as confusion, vomiting, headache, nausea, depression, disturbed sleep, moodiness, and amnesia.

However, even when the symptoms of a concussion appear to have gone, the brain is still not yet 100 percent normal, according to Dr. Maryse Lassonde, a neuropsychologist and the scientific director of the Quebec Nature and Technologies Granting Agency.

Dr. Lassonde previously worked alongside members of the Montreal Canadiens hockey team who suffered from severe head trauma, undertaking research into the long-term effects it can have on athletes.

She carried out visual and auditory tests among the athletes who suffered from concussion, as well as testing their brain chemistry, to evaluate the extent of damage to the brain after a severe hit.

The results indicate that there is abnormal brain wave activity for years after a concussion, as well partial wasting away of the motor pathways, which can lead to significant attention problems.

Her findings could have a considerable impact on the regulation of professional sports and the treatment of players who suffer from head trauma. It also highlights the need to prevent violence and aggression in professional sports.

Among older athletes, the lingering effects of concussion are even more marked.

A recent study was carried out comparing healthy athletes to those of the same age who suffered from a concussion 30 years ago. The results showed that those who experienced head trauma had symptoms similar to those of early Parkinson’s disease – as well as memory and attention deficits.

In addition, further tests revealed that the older athletes who had suffered from concussion experienced a thinning of the cortex in the same part of the brain that Alzheimer’s affects.

Lassonde added:

“That tells you that first of all, concussions lead to attention problems, which we can see using sophisticated techniques such as the EEG. This may also lead to motor problems in young athletes.This thinning correlated with memory decline and attention decline.”

Athletes who return to their sport too quickly following a concussion and subsequently suffer another one are at an extremely high risk of serious brain damage.

Lassonde concluded:

“If a child or any player has a concussion, they should be kept away from playing or doing any mental exercise until their symptoms abate. Concussions should not be taken lightly. We should really also follow former players in clinical settings to make sure they are not ageing prematurely in terms of cognition.”

A recent breakthrough in the detection of brain pathology related with these injuries was developed by researchers from UCLA, who were successfully able to identify abnormal tau proteins in retired NFL players using a brain-imaging tool – a protein also associated with Alzheimer’s. Previously the only way of identifying the protein was by an autopsy.

Written by Joseph Nordqvist